Apologies for the delay. The original version of this newsletter was chock full of jokes about Quibi being an inexplicably-still-in-business video streaming service. Unfortunately, in its final fit of disappointing its potential audience, Quibi decided to shut down before I could ever make fun of it. Rest in peace, Quibi. As Icarus, your ambition flew too close to the sun for your obvious conceptual flaw to handle.

THE QUIBI MEMORIAL JOHNNY MNEMONIC ISSUE

Before we begin, let me just say this: William Gibson is an unimpeachable pillar of science fiction writing. The path of technology culture - what it dresses like, sounds like, and thinks like - inarguably passes through Gibson. He’s the founding father of cyberpunk, which makes sense, since he invented the term “cyberspace.” When the X-Files did that season where they invited him and Stephen King to write episodes, his episode was better. Neuromancer will be sold in bookstores until there aren’t bookstores and, to what I can assume would be his glee, will be sold long after there are bookstores. He is an icon. He is a great writer.

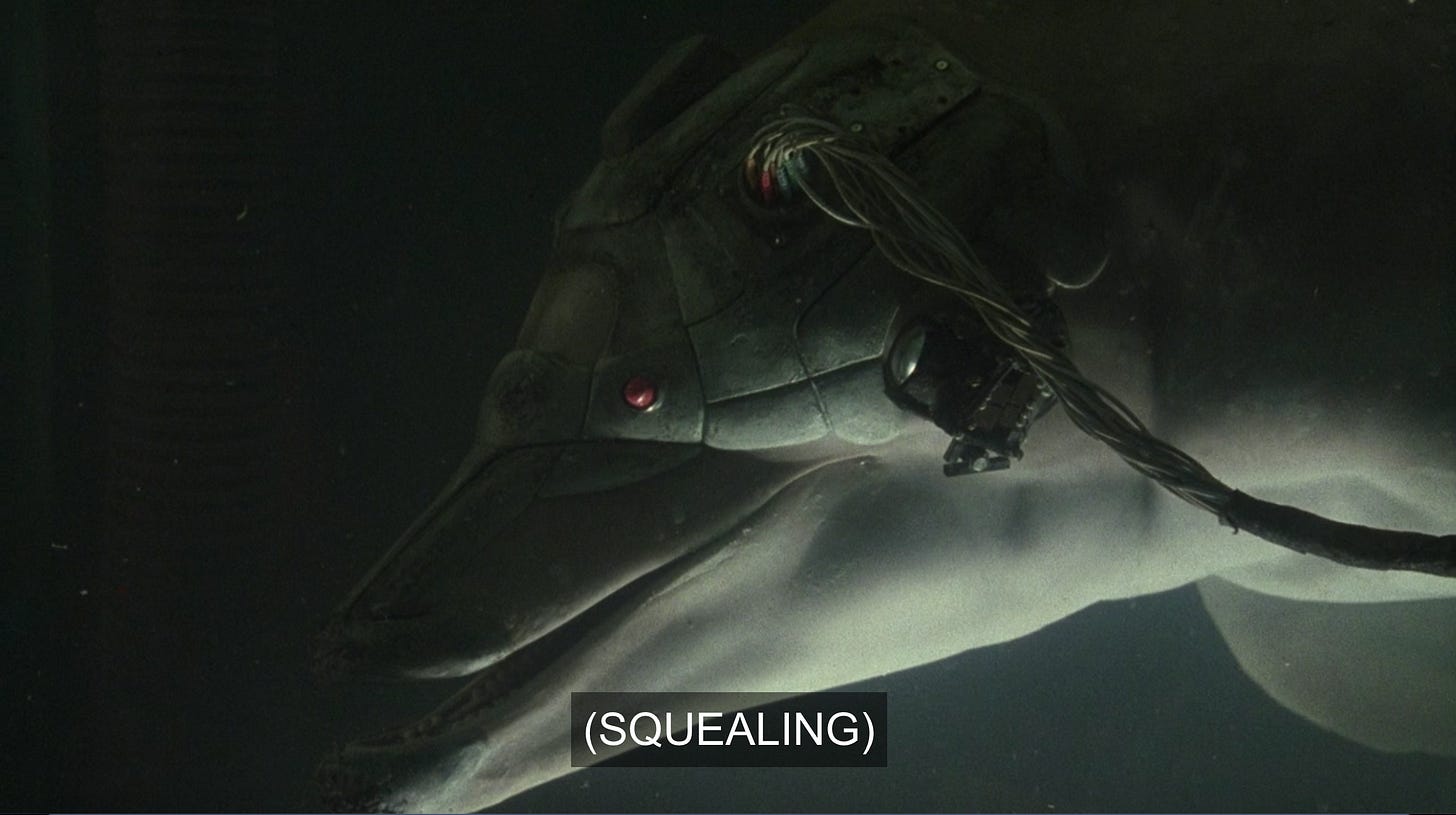

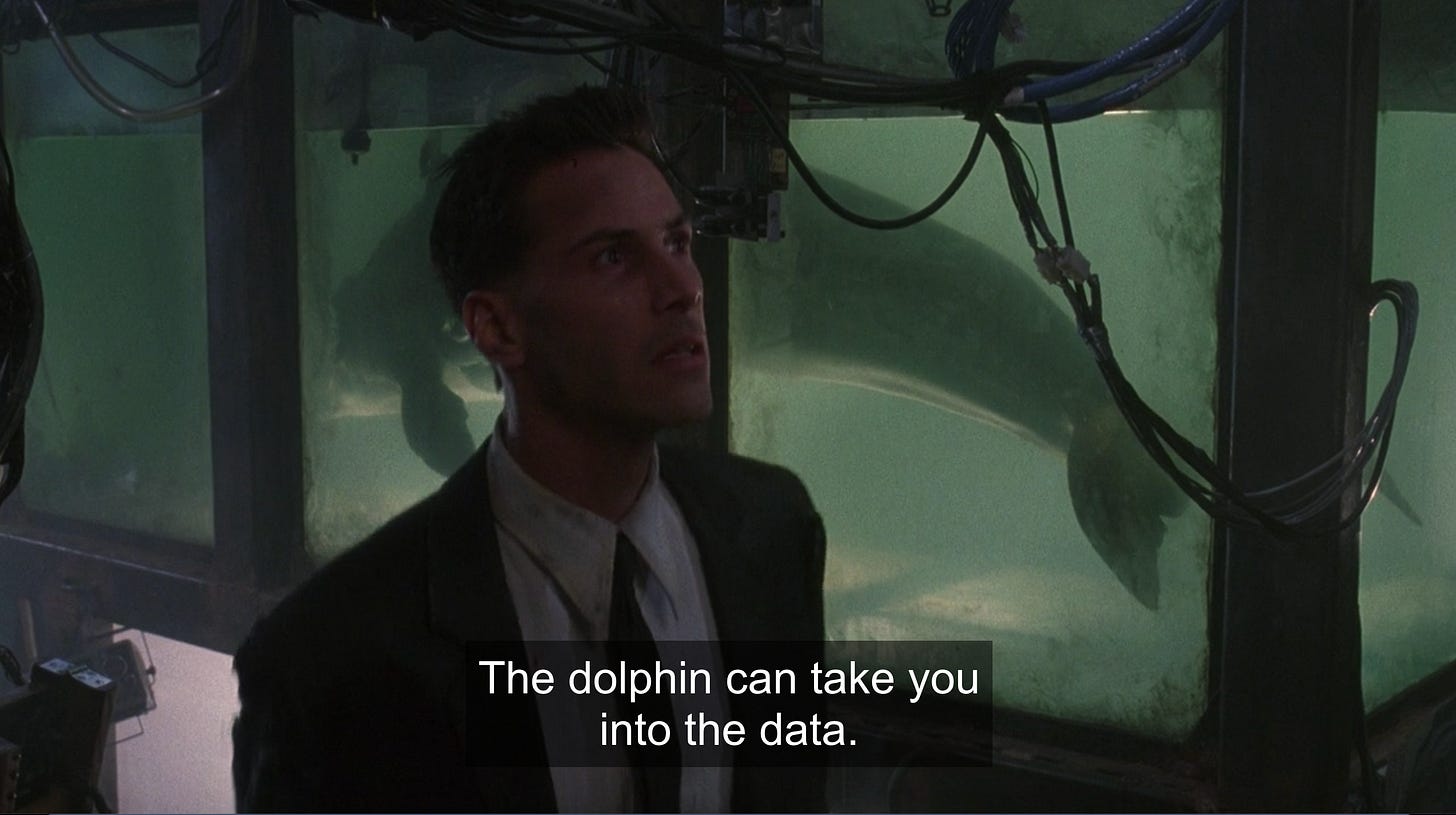

And in 1995, William Gibson got his first screenplay credit for Johnny Mnemonic, a dystopian futuristic noir where a code-breaking cyborg dolphin shows up unannounced in the last half hour to save the day. The dolphin’s name is Jones.

I want to be clear on this point: This is not a movie that has established code-breaking dolphins or any dolphins as characters. It isn’t a thing where animals have been integrated into society. There’s no wildlife at all in the movie. It takes place in Newark, where even pre-dystopia, there are few dolphins.

And, yet, in this movie a dolphin named Jones shows up, covered in wires.

Jones is a dolphin ex machina.

Johnny Mnemonic is a literal dolphin ex machina movie.

Johnny Mnemonic is based on a Gibson short story about Johnny, a data smuggler played by Keanu Reaves who hides data in a hard drive glued onto his brain. Due to a complicated series of events, if he doesn’t get a batch of data out of his brain, he will die.

This is a pretty major design flaw.

Not the complicated “download the data or you’ll die” thing--Johnny Mnemonic carefully walks you to that plot point, explaining things like storage limits and synaptic leakage. The design flaw is that Johnny is smuggling data in a hard drive glued onto his brain in the first place.

The internet exists in this movie. That’s a good way to send data from place to place. When Johnny uploads the data into his brain, he does it in a hotel room where the data thieves brought the data on a single CD. That also seems like a good way to get data from place to place. Someone figured out how to smuggle a dolphin named Jones to inland New Jersey. In a world that manages cyborg dolphin couriers, brain courier seems like a completely unnecessary job.

Seems much easier to smuggle

There are a ton of ideas for new technology in Johnny Mnemonic, but not much thought about why someone would use any of it, how popular it would be, or how the society would be reconstructed around it. It’s as though the world is in beta, waiting to figure out how people would use its ideas, how they would break the world, break the user and break each other. It’s missing the sense that technology has an inevitable effect on the world around it, intended and otherwise.

In a gritty world where technology is supposed to be profoundly important, it’s somehow of no importance whatsoever.

Technology only exists to create consequences. They are inevitable, even when we don’t know them in advance. Good movies about technology - and good technology - takes that into account. The inevitability and the unintended effects that make these futures interesting.

In an age where something like social media has so pervasively restructured society, it’s tough to watch a movie like Johnny Mnemonic about advanced technology that doesn’t. If your future has jet packs, it doesn’t have parking garages. Johnny Mnemonic has a lot of parking garages.

Johnny Mnemonic cures death and it’s a blink-and-you-miss-it plot point. In Johnny Mnemonic, you can upload your consciousness to the internet before you die and live on as an artificially intelligent ghost, haunting the web. It’s apparently common enough that you can get Swiss citizenship.

And yet, society continues along as normal. People fear death in Johnny Mnemonic. Why? Why hasn’t the job market been decimated by a workforce who could live on wages that don’t have to support food or rent or clothing? Why aren’t the internet people the ones smuggling the data?

Jones becomes sort of a mascot for the technology that should run amok not running amok. Somehow, when time comes for Jones to be introduced, Johnny is as blindsided as the audience that there’s been a hyper-intelligent cyborg dolphin hanging out in New Jersey this whole time. The movie seems to be surprised Jones could be kept a secret. The movie is right.

If you live in a world with cybernetic dolphin codebreakers, you live in a world where it’s at least believable that there are cybernetic dolphin codebreakers.

If there are dolphins with brain implants to help them solve codes, there are parents getting kids brain implants to help them solve algebra. Someone, somewhere, tried to sell pets that could communicate in English, before everyone realized how horrifying it would be to talk to someone you just got spayed. In 1995, when Johnny Mnemonic came out, the cartoon character Space Ghost was already hosting a televised talk show. In the future, if someone can make a dolphin smarter than a person, someone else has, at minimum, created a hamster smart enough for a pilot on TNT.

If Jones is somehow the best codebreaker, and the world needs codebreakers - both appear to be true in Johnny Mnemonic - there is going to be more than one Jones. Jones isn’t a secret; he’s a top of the line product.

This is a weird problem for William Gibson to have. Part of the whole cyberpunk ethos was that technology and capitalism would create a fascinating new underclass beneath the utopias they created. Corporations would usurp the power of governments. Technology would bleed into the public without regard for safety. It’s a genre about unintended consequence, bound by neon and noir. It’s not a genre where any technology is kept a secret. It’s one where every technology is bled dry for every ounce of profit.

None of this is a problem in the short story “Johnny Mnemonic,” which came out around fifteen years earlier. “Johnny Mnemonic,” the story, is a tonal sketch of a world where people are as casual about remodeling themselves as living rooms. Lovers change their appearance to look like each other. Tough guys get fangs or muscle implants. It’s so normal that the story is pretty nonchalant about Jones - if we’re customizing ourselves, of course we’re customizing our wildlife. It’s body horror threaded together with barely enough plot for a short story. It’s the kind of thing that can work as a short story - the narrator focusing on the plot is a pretext for how unsettling it would be to treat that world as normal and tell a story less exciting than the world.

Where the movie should have leaned into the body horror, it leaned into the plot. A plot that probably made more sense in the ‘80s, when floppy disks couldn’t hold that much data and there was no broadband.

When there are consequences to technology in Johnny Mnemonic, it’s not because of the march of progress. The second act reveal comes when an epidemic, all but forgotten since in the opening scroll, is the result of technology - we’re never told what technology, specifically. But that’s a plot point, rather than the inevitable end of technology remodeling society. Gibson may as well have said technology causes werewolves or tooth decay.

There a bunch of reasons to root for Johnny Mnemonic to be better. Dolph Lungren throws himself into the role of a cybernetic religious zealot (why the tagline wasn’t “A Dolphin and Dolph in Johnny Mnemonic” is beyond me). Henry Rollins plays the person you just sort of assume Henry Rollins is. And Keanu Reaves plays the template of all his best characters - likable erstwhile antihero who a fantastical world happens to.

But in the end, it’s a movie that feels less like it takes place in the future, and more like it took two scoops of the future, dumped it in the present, and never waited for it to dissolve.

The joke about Quibi was going to work like this: The difference between science and technology is that technology has applications. Technology without a use case either doesn’t exist or is Quibi. Quibi, rudely, proved my point before I got to make it. Johnny Mnemonic is a Quibi world. All good Quibis come to an end. And few good Quibi’s come to a start.

Comments? Tweet me at @joeuchill.

Subscribe! When we have a critical mass, we’ll start throwing Netflix parties for paid subscribers.